Defeating Terrorism – Why the Tamil Tigers Lost Eelam…And How Sri Lanka Won the War

March 11, 2011

The 2009 defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the death of their supreme leader Velupillai Prabhakaran at the hands of the Sri Lankan Army can be traced to specific decisions made by both Prabhakaran and Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa. But before those decisions can be laid out and analyzed, a brief history of the Tamil experience in Sri Lanka is necessary.

A History of Discrimination, the Tamils

March 11, 2011

The 2009 defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the death of their supreme leader Velupillai Prabhakaran at the hands of the Sri Lankan Army can be traced to specific decisions made by both Prabhakaran and Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa. But before those decisions can be laid out and analyzed, a brief history of the Tamil experience in Sri Lanka is necessary.

A History of Discrimination, the Tamils

Jaffna, a somnolent, leafy town in the north of Sri Lanka, is the heartland of the indigenous Tamils who came to Sri Lanka more than 2,000 years ago. Their community is distinct from that of the southern Indian Tamils who came to Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) as indentured labor during the five centuries when the island was the colony of a succession of European states. The British, the last of the colonial rulers, adopted a neutral policy towards the Tamils and Ceylon’s more numerous (by four times) Sinhalese population.

Sri Lanka Political Map Once freedom arrived in 1948, the majority Sinhala population decided that it their time to rule the island. In 1956, they did away with both English and Tamil as official languages, retaining only Sinhala as the medium for both administration as well as education.

Sri Lanka Political Map Once freedom arrived in 1948, the majority Sinhala population decided that it their time to rule the island. In 1956, they did away with both English and Tamil as official languages, retaining only Sinhala as the medium for both administration as well as education.

As is evident from their diaspora, the Tamils are a community that prize education and achievement if given the chance. During the years of British rule, they took to English with a felicity that was not matched by the Sinhala, the overwhelming majority of whom belonged to the “lower castes.”

Less than a twentieth of the Sinhala population was “high caste,” and it was only this sliver of feudal landholders who had access to the language of their colonial masters. And because the disadvantaged were shut out from language study, class exclusivism within the Sinhala English-speaking community continued. This contrasts with India where, at the same time and despite official disapproval, more and more educational facilities retained the English language. By the 1960s, knowledge of English began to spread into the middle classes.

Language as a Discriminatory Tool

Restricting government jobs only to those fluent in Sinhala (i.e. the Tamils) would not have been as critical a factor had Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) a substantial private sector presence. Unfortunately, many of the British-educated Sinhala leaders who took charge of the country post-1948 shared the Fabian socialist ideology of India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. They regarded private business as evil and the generating of private profit as criminal.

In particular, Prime Minister Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike, an elite Sinhala Christian leader from the southern part of the country, copied Nehru in imposing severe curbs on the private sector at the same time as he restricted employment in the state sector to Tamils by enforcing a “Sinhala Only” policy in 1956. Proficiency in Sinhalese was made mandatory for employment in government or even to gain admission to schools and colleges.

Thus far, because of the wider spread of English within the Tamil population, they had been represented in both state and especially educational units far in excess of their one-fifth share in the population, a situation that was abruptly reversed once Sinhala became the only official language of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon). Now Tamils had nowhere to turn to for jobs once the state sector shut its doors in their faces from the mid-1950s onwards. Large-scale private industry had been pushed to near-extinction. The fissure between Sinhala and Tamil that has so bedeviled the country began to deepen from this time onwards.

Although the use of violence is an unacceptable means of changing the status quo, it must be recognized that the Tamils in Sri Lanka had genuine grievances. The 1983 violence had been preceded by more than two decades of discrimination against them.

Although the use of violence is an unacceptable means of changing the status quo, it must be recognized that the Tamils in Sri Lanka had genuine grievances. The 1983 violence had been preceded by more than two decades of discrimination against them. Under the terms of an agreement entered into in October 1964 between then-Prime Minister of Sri Lanka Sirimavo Bandarakanaike, the wife of by then deceased Prime Minister Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike, and Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri of India, more than 200,000 Tamil plantation workers were forcibly repatriated to India, to live in squalor as refugees.

Criticality of the English Language

Had the Sinhala chauvinists pandered to by the Bandaranaikes and their successors had the wisdom to retain English (as Lal Bahadur Shastri did in India in 1965), much of the agony that was subsequently the lot of their country could have been averted. The holding of entrance examinations to government jobs in English would have taken the edge off Tamil anger at the discrimination shown against their ancient language in a country that had been their home for at least 2,000 years.

Rise of the Tigers

Because of governmental restrictions, young Tamils were unable to migrate except to India, a country even poorer than their own. Consequently, they were eager fodder for the practitioners of violence who convinced many Tamils that they could expect no justice from the Sinhala population.

And although there appear to be few – if any – genetic differences between Sinhalas and Tamils in Sri Lanka, Sinhala chauvinists had over the decades adopted entire pages from the textbooks of 1930s Germany and fashioned a narrative whereby they were “Aryan” and “civilized” (i.e. Buddhist) as opposed to the “Dravidian” and “pagan” (i.e. Hindu) Tamils.

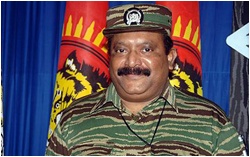

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) assisted such fanatics because of its provocative campaign that denigrated Buddhism and desecrated holy places belonging to that ancient faith. For the LTTE’s leader, LTTE Leader Velupillai Prabhakaran Prabhakaran (pronounced “Pirabakaran”), each dose of Sinhala rage against the Tamils was fresh oxygen that enabled him to increase both the recruitment of Tamil fighters and the monetary donations to the LTTE.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) assisted such fanatics because of its provocative campaign that denigrated Buddhism and desecrated holy places belonging to that ancient faith. For the LTTE’s leader, LTTE Leader Velupillai Prabhakaran Prabhakaran (pronounced “Pirabakaran”), each dose of Sinhala rage against the Tamils was fresh oxygen that enabled him to increase both the recruitment of Tamil fighters and the monetary donations to the LTTE.

The meandering path of Prabhakaran’s revolt against the Sri Lankan state and his efforts at securing recognition for the small kingdom that he created in the north and east of the country have been covered at length by numerous historians and it would be repetitive to go through the same events in this narrative. Suffice it to say that by the end of the 1980s, the LTTE had – by the simple expedient of killing off any rival – made itself (in its words) “the sole representative” of the violent struggle for an independent Tamil homeland known as “Eelam” to be created out of the north and east of the country.

Fast forward to May 18, 2009, when the Sri Lankan army announced that LTTE supreme leader Prabhakaran was killed in the campaign that had been waged against his organization by Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa. It was claimed, again by Sri Lankan army leaders that he had been killed “while trying to escape” an army platoon that had surrounded him and a half-dozen of his personal bodyguards. Prabhakaran’s son Charles was also killed while presumably “trying to escape” as well. There was no way of independently verifying the circumstances of his death since the Sri Lankan army speedily cremated the body. With the loss of their leader, the LTTE disintegrated and almost all their senior commanders were subsequently killed or captured.

In a campaign that lasted just under 30 months, the Sri Lankan military had eliminated one of the world’s most effective terror organizations and the one that had perfected the use of suicide bombers. How and why such a collapse came about is important for the lessons that it contains for other countries battling similar insurgencies

In a campaign that lasted just under 30 months, the Sri Lankan military had eliminated one of the world’s most effective terror organizations and the one that had perfected the use of suicide bombers.

Velupillai Prabhakaran, the LTTE’s founder and supreme leader first came to public attention in 1975, when he shot and killed the mayor of Jaffna, Alfred Duraiappah, another Tamil. It was the start of a pattern that was to continue for the rest of Prabhakaran’s life – killing any Tamil whom he regarded as a threat. Prabhakaran escaped into the jungles of the Vanni region of northern Sri Lanka where his charisma speedily secured for him the allegiance of some two-dozen young Tamil fighters. They conducted raids on government establishments and officials in the area. In 1983, the LTTE came of age. On July 24 that year, a sixteen-man squad ambushed and killed thirteen Sri Lankan soldiers through the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The shock waves from this assault spread within the majority Sinhala community and – clearly with the connivance of the J.R. Jawaradene government then in office – armed thugs began a pogrom against the Tamil population. Sinhala gangs killed nearly 5,000 Tamils in these spasms of bloodletting, often as the police looked on.

More than 3,000 of these murders took place in the capital city of Colombo. The author’s own parents were among those whose houses were entered into by Sinhala mobs searching for Tamils during that month of carnage. Fortunately, the invaders turned away upon seeing a large bust of Lord Buddha on the mantelpiece in the front room. The 1983 riots laid waste to any remaining thought in the Tamil community that a united Sri Lanka could be possible, provided incentive to Tamil groups that had thus far not endorsed violence against the Sinhala establishment, and provided a sense of righteousness to those Tamil groups already employing violence.

Another key consequence of the riots was to persuade Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India that the interests of her country mandated a steep increase in direct support for the Tamil insurgents, in particular the LTTE. From that time until 1987 (when President Jayawardene signed a pact with Indira Gandhi’s son and successor, Rajiv), there was a steady flow of cash, weapons and training, mostly to the LTTE. More than concern for the Tamils, what was worrying Gandhi was President Jayawardene’s closeness to a triumvirate of countries that, at the time, were very close – the United States, China and Pakistan. The jihad against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan had drawn the three together and, to the Indian government, they seemed to be moving in unison to diminish Indian influence in Sri Lanka by showing that Delhi could not protect the Tamil population.

Another key consequence of the riots was to persuade Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India that the interests of her country mandated a steep increase in direct support for the Tamil insurgents, in particular the LTTE. From that time until 1987 (when President Jayawardene signed a pact with Indira Gandhi’s son and successor, Rajiv), there was a steady flow of cash, weapons and training, mostly to the LTTE. More than concern for the Tamils, what was worrying Gandhi was President Jayawardene’s closeness to a triumvirate of countries that, at the time, were very close – the United States, China and Pakistan. The jihad against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan had drawn the three together and, to the Indian government, they seemed to be moving in unison to diminish Indian influence in Sri Lanka by showing that Delhi could not protect the Tamil population.

1987 – Indian Intervention Rescues the Tigers

In 1987, similar success by the Sri Lankan army against the LTTE was checked by India’s entry into the fray, worried as Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was that Sri Lanka under Jayawardene would form an alliance with the United States-China-Pakistan triumvirate, thereby providing the latter with facilities less than 20 kilometers off India’s southern coast. As mentioned earlier, the fear of a Sri Lankan alignment with countries seen as hostile to India was decisive in Indira Gandhi’s decision to arm, fund and train the LTTE – a policy that had a huge blowback in subsequent years, including the 1992 assassination of Indira’s son, Rajiv Gandhi, by a female LTTE suicide bomber. This led to the proscribing of the LTTE as a terrorist organization in India and played into the hands of the Sri Lankan government. From then onwards, India backed Colombo’s campaign against the LTTE.

[T]he fear of a Sri Lankan alignment with countries seen as hostile to India was decisive in Indira Gandhi’s decision to arm, fund and train the LTTE – a policy that had a huge blowback in subsequent years, including the 1992 assassination of Indira’s son, Rajiv Gandhi, by a female LTTE suicide bomber.

The LTTE had thrived on a policy of using cease-fires and “peace agreements” to recover from battlefield losses. In 1987, the LTTE had been rescued from defeat by the intervention of the Indian government, which dispatched the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) to effectively partition Sri Lanka into an LTTE-held area and the rest of the country. Soon afterward, however Prabhakaran’s insistence on formal independence clashed with India’s disinclination to support a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka (for fear that it would provide incentive to some of India’s own restless ethnic groups) led to clashes between the LTTE and the IPKF. This got the attention of the newly elected President of Sri Lanka, Ranasinghe Premadasa, who was convinced that predominantly Hindu India sought to extinguish Buddhism in Sri Lanka much as it had been driven out of India.

[Premadasa’s assassination] was a real lesson to those who believed that they can ride a terror tiger and dismount at will.

Premadasa began to supply weapons and cash to the LTTE (as long as they were attacking Indian soldiers) and simultaneously called for the immediate withdrawal of the IPKF, which was agreed to by the New Delhi government that had taken over in the wake of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in 1991. Of course, once the Indian force departed, the LTTE turned again on the Sri Lankan army and on Premadasa himself, assassinating him in 1993. It was a real lesson to those who believed that they can ride a terror tiger and dismount at will.

The “Stop, Go, Stop” policy pursued by successive Sri Lankan administrations in dealing with the LTTE is a textbook example of how not to deal with an insurgency. Each time battlefield losses inflicted by the Sri Lankan military caused a crisis in the ranks the LTTE would use the mediation of selected NGOs to “open peace talks” aimed at a cease-fire that would enable the organization to replenish its supplies of weapons, cash and manpower. Once these reached acceptable levels, the “cease-fire” would be broken, and the military campaign would begin again.

2001 – Norway Rescues the Tigers From Sure Defeat

In 2001, as in 1987, just when the LTTE seemed on the precipice of disaster, a white knight appeared. This was Norway, whose propensity for the embrace of unlikely causes seems to rise in proportion to its oil revenues. The articulate and widely dispersed Tamil diaspora helped keep going the perception of genocide, scarred as most of them had been by memories of the 1983 riots and the long-running discrimination at the hands of the Sinhalese. During that time, Prabhakaran’s band of fighters had dwindled below 3,000 and money to buy weapons was lacking. Fighting had broken out between the Jaffna and the Batticaloa LTTE contingents and the Sri Lankan military blockade meant that fuel and even food was low. The Sri Lankan army was at Prabhakaran’s doorstep for the first time since 1987. But then the emissaries from Oslo came to the LTTE’s rescue.

The 9/11 attacks ought to have made chancelleries in Europe all too aware of the risks attendant to backing groups engaged in violent struggle. And unlike in 1987, this time around (because of the Rajiv Gandhi assassination), India was no longer assisting the LTTE. In fact, the LTTE’s only Indian support came from a clutch of politicians in the state of Tamil Nadu that had links with the LTTE since the 1980s and who were known to be the recipients of LTTE funding funneled through the head of the Paris LTTE station, Manoharan. These politicians were, however, gadflies and even if they had not been, India at the start of the 21st century was not quite the regional power that it had been in the 1980s, for by now both China as well as the United States were regionally active, chiefly because of the realization that Sri Lanka’s location made it the pivot of the Indian Ocean.

The “Stop, Go, Stop” policy pursued by successive Sri Lankan administrations in dealing with the LTTE is a textbook example of how not to deal with an insurgency.

Soon after the 9/11 attacks on the United States homeland, Prabhakaran replaced the staff in his European outreach offices in Europe. Sent home were the old fighters and, in their stead, in came natives of Europe or North America whose liberal consciences were activated at their perceived role as warriors against Tamil genocide.

Aware of the influence European human rights NGOs, Prabhakaran enlisted their assistance in portraying the LTTE’s war against the Sri Lankan state as an ethnic conflict between Sinhala and Tamil. This is ironic in that at no stage in his career had Prabhakaran ever tested his popularity among the Tamils with a free election. Instead, in a constant revisiting of the 1983 anti-Tamil carnage, the LTTE’s war was cast as a defense against an attempted genocide despite the fact that it was only the LTTE by then that was initiating bloodshed.

Now that he had the Norwegians on his side, Prabhakaran declared a unilateral ceasefire on Christmas Eve in 2001 and thereafter began signaling his desire to work out a “comprehensive and just peace.” With zeal, the Norwegians persuaded the rest of Scandinavia to back them in their efforts at yet another Sri Lankan ceasefire and they were soon joined in this effort by key European Union countries including Germany. Such international pressure proved too much for Sri Lankan President Chandrika Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe to resist and a ceasefire agreement, signed by the Wickremasinghe and the LTTE head Prabhakaran, came into effect that lifted the blockade of the LTTE-held areas and allowed the LTTE access to their foreign donations needed to stockpile weapons and ammunition.

By formally agreeing to a negotiated cease-fire arranged by foreign countries, the Sri Lankan government gave Prabhakaran’s LTTE movement parity with the state, a humiliating blow to the Sri Lankan army ranks fighting the terrorists. Once the cease-fire went into effect, the army units deployed in the LTTE-held areas of the north and east were confined to barracks while LTTE units moved openly and subjected the soldiers to frequent verbal abuse and, on occasion, live fire. Army anger at their neutering during the cease-fire played a role in the ruthless tactics employed by in 2009, especially during the closing days of the campaign against the Tigers.

At the same time, Prabhakaran also suffered setbacks. Two stand out. The first was the defection of one of his top commanders, Karuna, to the Sri Lankan army in 2004. Prabhakaran was known to harbor suspicion about his commanders’ loyalties and many of those that crossed his mind in this way were killed often after prolonged torture. Karuna had been getting indications that he was next and before the blow fell he escaped along with nearly 2,000 fighters. This was the first major split in the LTTE and was indicative of Prabhakaran’s transformation from a guerrilla leader popular with his forces into a suspicious autocrat who created a system of parallel “silos” – army, navy and political – each reporting solely to him and which had minimal coordination with each other. The second setback was the 2005 tsunami that disproportionately wreaked havoc on the LTTE-held areas of the country.

The cease-fire kept Sri Lankan government and military forces from operating in the LTTE-held zones while LTTE units, not being part of a recognized government, were free to move into the rest of the country raising money and recruiting new fighters. And in another fit of northern European generosity, the Norwegians ensured that the Sri Lankan government paid salaries and subsidies in the LTTE-held areas. Meanwhile, in India’s Tamil Nadu state, selected “leaders of public opinion” were provided with LTTE money to ensure that they would continue to demand that the Indian government back the LTTE in the conflict.

Once the 2002 ceasefire went into effect, Prabhakaran summoned his top commanders to the Vanni area of Sri Lanka in the heart of the LTTE controlled area and told them that they had to prepare their cadres to launch a fresh war in five years by which time he expected the LTTE to have attained parity with the Sri Lankan military. Present at the meeting were head of LTTE special operations Shanmugalingam Sivashankar (nom de guerre Pottu Amman), head of LTTE naval forces Thillaiyampalam Sivanesan (nom de guerre Colonel Soosai), and LTTE political officials Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan (nom de guerre Colonel Karuna Amman) and Rasaiah Parthipan (nom de guerre Lt. Col. Thileepan). Their unity ensured that Prabhakaran’s plan to reestablish the LTTE’s strength would move forward assisted as it was by the money that had begun flowing in from numerous foreign NGOs, which were collecting the cash “for humanitarian purposes.”

… Prabhakaran’s plan to reestablish the LTTE’s strength would move forward assisted as it was by the money that had begun flowing in from numerous foreign NGOs, which were collecting the cash “for humanitarian purposes.”

It was during ceasefire period of 2002-2006 that Prabhakaran emerged as, effectively, the ruler of almost a third of the Sri Lankan coast and a fourth of that country’s land area. Of course, democracy was far away from his agenda, despite his frequent references to the term in interaction with a growing band of European and (subsequently, but to a much lesser extent) American admirers and supporters. Those living in the LTTE-held areas that had relatives in North America or Europe were “encouraged” to “request” their brethren to contribute generously to the cause. Such funds were immediately diverted towards the creation of an air force and a navy as well as for the purchase of mortars, artillery and even armor-plated vehicles. By the time of the 2005 presidential elections, the prospect of the LTTE gaining parity with the Sri Lankan military did not seem as outlandish as it had in 2001.

2005 – The Tide Turns Against the LTTE

Largely because of a poll boycott enforced by the LTTE that kept Tamils from casting their ballots in favor of pro-peace candidate Ranil Wickremasinghe of the United National Party, the United People’s Freedom Alliance candidate, Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa (whose own Sri Lanka Freedom Party is part of the alliance), achieved a narrow victory in the November 2005 election. For the first time, a rural Sinhala politician was president of the country and, within a few months, began replacing the urban elite that until then had dominated the upper echelons of the Sinhala establishment.

Largely because of a poll boycott enforced by the LTTE that kept Tamils from casting their ballots in favor of pro-peace candidate Ranil Wickremasinghe of the United National Party, the United People’s Freedom Alliance candidate, Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa (whose own Sri Lanka Freedom Party is part of the alliance), achieved a narrow victory in the November 2005 election. For the first time, a rural Sinhala politician was president of the country and, within a few months, began replacing the urban elite that until then had dominated the upper echelons of the Sinhala establishment.

It is true that President Ranasinghe Premadasa (1989-1993) was from a rural area, but he had contented himself with being the symbolic face of the underclass, with almost all other top posts going to the Sinhala (and a few Tamil) elite. In contrast, President Rajapaksa understood that he needed a team congruent with his interests and motivation to assist him in implementing the policies he favored, which was the protection of the country’s Buddhist primacy and faster development of the economy. By the end of 2006, more than 40 percent of top jobs had gone to the rural Sinhala segment of the population for the first time in the history of a country where they formed 70% of the population

President Rajapaksa inherited a divided country with LTTE head Prabhakaran being in effective charge of a quarter of its land area and a third of its coast. He faced a militarily rejuvenated LTTE that was in conflict with his dispirited and underfunded military. He initially took the line of least resistance, telling the army to remain passive in the face of increased LTTE attacks on civilians. At the same time, however, he began to personally attend each of the weekly meetings of the National Security Council and appointed his brother, Gotebhaya, defense secretary.

Rajapaksa secured a substantial increase in funding for the military and boosted its strength with some 80,000 additional troops by the close of 2006, the year when Prabhakaran decided that his LTTE forces were strong enough to break the 2002 cease fire. Prabhakaran’s offensive, along with his decision to drive Sinhala farmers out of the Eastern province by flooding their lands through the opening of sluice gates at dams in the region. The moves galvanized Sinhala opinion behind a new offensive against the LTTE.

Rajapaksa secured a substantial increase in funding for the military and boosted its strength with some 80,000 additional troops by the close of 2006, the year when Prabhakaran decided that his LTTE forces were strong enough to break the 2002 cease fire. Prabhakaran’s offensive, along with his decision to drive Sinhala farmers out of the Eastern province by flooding their lands through the opening of sluice gates at dams in the region. The moves galvanized Sinhala opinion behind a new offensive against the LTTE.

Rajapaksa promised his troops that the war would end only with the LTTE’s elimination and Prabhakaran’s capture or death. As Sinhala politicians had made similar statements in the past, Prabhakaran did not take this latest vow seriously.

Had Prabhakaran paid closer attention to Rajapaksa’s mode of operation, he may have discerned that the rural leader was very different from the diplomatic circuit-loving Sri Lankan prime ministers and presidents of the past. For a start, Rajapaksa began to nudge the local media into ceasing the flood of negative reporting on the military that had been the norm for more than a decade. Secondly, those NGOs that had favored peace talks and conciliation with the LTTE were accustomed to easy access to the Sri Lankan head of state now found their access to the President’s House blocked. And, unlike his predecessors, Rajapaksa refused to accept the Norwegian “facilitators” protecting the LTTE as the final authority.

Not used to having “children” (which is the way those from underdeveloped countries were viewed by several officials from the developed world) reject their orders, the Norwegians made sure that the EU publicly expressed its disapproval of Rajapaksa’s refusal to comply with Norway’s recommendations. Undeterred, the new Sri Lankan president shrugged his shoulders and continued with the military campaign.

2007 – The Final War Against the Tigers Kicks Off

As defense secretary, Gotebhaya Rajapaksa proved to be an effective manager. While the Sri Lankan army advanced northward, he directed units of the air force and the navy to block retreating LTTE units from regrouping in the eastern provinces as they had done many times in the past. Meanwhile, President Rajapaksa followed a policy of accepting assistance – in any form and quantity – from wherever he could find it. He gratefully accepted American signals intelligence that pinpointed the location of LTTE boats bringing weapons into Jaffna. Many, if not most, of these boats were hunted down and destroyed. Prabhakaran also made good use of extensive satellite imagery provided by India that revealed LTTE positions in the densely wooded north, and he accepted huge loads of armaments from China and Pakistan.

The entire time, President Rajapaksa was increasing the strength of the Sri Lankan military, especially the army which almost doubled in size to more than 500,000 including auxiliaries between 2005 to 2007, the year when the final battle to annihilate the LTTE began.

Adopting the combat tenets of counterinsurgency warfare, the Sri Lankan army ceased seeking decisive engagements with LTTE forces. Instead, small stealthy army units … surprise[d] LTTE units in their rear areas which, in addition to killing LTTE fighters, sowed confusion and panic within the heretofore confident LTTE ranks.

While the takeover of the eastern provinces had been accomplished without the loss of a single member of the Sri Lankan military, the push to the north entailed casualties but these were minimized by the Sri Lankan army’s use of unconventional tactics. In the past, it was the LTTE that was known for conducting quick strikes against larger army units and then withdrawing before the army’s superior firepower could be brought to bear. From 2007 onward, such ambushes were more likely to be conducted by the Sri Lankan army against LTTE units.

Adopting the combat tenets of counterinsurgency warfare, the Sri Lankan army ceased seeking decisive engagements with LTTE forces. Instead, small stealthy army units utilized satellite and signals intelligence to surprise LTTE units in their rear areas, which, in addition to killing LTTE fighters, sowed confusion and panic within the heretofore confident LTTE ranks. The LTTE did carry out a few major attacks during this time, such as at Anuradhapura in 2008, but these did not lead to a ceasefire – something that would have been expected in the past. Instead, they provoked the government to redouble its efforts. Indeed, the fact that he had become a “war president” helped Rajapaksa to consolidate his government adding several splinter parties to his coalition and securing a comfortable parliamentary majority for his party.

Prabhakaran’s personal dictatorship and refusal to tolerate anyone other than sycophants to be close to him had so demoralized LTTE commanders that a few even surrendered to the government.

The LTTE’s retreat to their strongholds at Jaffna and the Vanni as well as to Prabhakaran’s home base in Killinochi served to illustrate the fact that he was no longer viewed the supreme leader of the Tamils, even by his own cadre. His personal dictatorship and refusal to tolerate anyone other than sycophants to be close to him had so demoralized LTTE commanders that a few even surrendered to the government. His ruthless murder of perceived rivals – often after prolonged tortured – paralyzed many of his closest subordinates greatly harming the LTTE’s ability to fight the Sri Lankan army.

Having bought into the Norwegian story that the LTTE represented the entirety of Sri Lanka’s Tamil community, only the Europeans looked on with disapproval at the Sri Lankan government’s battlefield successes. In fact, less than 30% of Sri Lanka’s Tamil population lived in LTTE-controlled areas even during Prabhakaran’s 2002-2005 heyday, thereby making moot any partition of the country on ethnic lines

Having bought into the Norwegian story that the LTTE represented the entirety of Sri Lanka’s Tamil community, only the Europeans looked on with disapproval at the Sri Lankan government’s battlefield successes. In fact, less than 30% of Sri Lanka’s Tamil population lived in LTTE-controlled areas even during Prabhakaran’s 2002-2005 heyday, thereby making moot any partition of the country on ethnic lines

2009 – The Final Phase and the LTTE’s Destruction

By March 2009, the Sri Lankan military was into the final phase of its destruction of the LTTE. The LTTE’s desperate situation was matched in intensity by the diplomatic pressure brought by Norway and other European countries on President Rajapaksa to support a cease-fire. The Rajapaksa government, however, had ensured an effective back channel with the one country that had the motivation to directly intervene in favor of the LTTE, India. President Rajapaksa had appointed his brother to keep the Indian government of Manmohan Singh informed about Sri Lanka’s military moves. The result was that although a few pro forma admonitions were issued by New Delhi (because of pressure from one of the Congress Party’s coalition partners, the Dravida Munnettra Kazhagam(DMK) party, which was historically close to the LTTE and its goals.

The critical factor in the Sri Lanka’s 2009 victory was the diplomatic coup secured by President Rajapaksa. For the first time, Norway and the EU were prevented for imposing a cease-fire that would allow the LTTE to regroup and rearm.

Overall, India stood aside while the LTTE was finally defeated in May 2009. After 30 years of insurgency, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam had been annihilated. An ugly result given the fact that the LTTE was often criticized for its use of human shields, while the Sri Lankan military did not allow concerns for collateral civilian casualties to get in the way of its artillery targeting during the final weeks of the war.

China and India Were Decisive Factors in the Sri Lankan Victory

LTTE head Prabhakaran’s refusal to be satisfied with the territory that had been given to him by the terms of the 2002 ceasefire was backstopped by his belief that no matter how hard hit his forces were by the Sri Lankan military, Norway and the EU could be courted on to secure a cease-fire that would allow his Tigers respite. Prabhakaran wanted more territory and legal recognition for an independent Tamil Eelam, a demand that even peace-minded Prime Minister Wickremasinghe could not deliver in his day.

The critical factor in the Sri Lankan government’s 2009 victory over the LTTE was the diplomatic coup secured by President Rajapaksa. For the first time, Norway and the EU were prevented from imposing a cease-fire that would allow the LTTE to regroup and rearm. Indeed, Prabhakaran believed nearly until the end that a cease-fire would be imposed. The essential element of the plan was Rajapaksa’s securing India’s tacit backing and China’s open support for his war aims.

M.D. Nalapat is Vice-Chair of the Manipal Advanced Research Group and UNESCO Peace Chair as well as Professor of Geopolitics at Manipal University in India’s Karnataka State.

[The opinions expressed in JINSA Global Briefings are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA).]