President Morsi Acts Out Egypt’s Tragedy

By David P. Goldman

JINSA Fellow

By David P. Goldman

JINSA Fellow

How should we understand the apparently erratic behavior of Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi? In September, he seemed an unreliable ally, if an ally at all, after his tardy and diffident response to mob attacks on America’s Cairo embassy. Morsi rose sharply in Western esteem after the November 21 Gaza ceasefire, only to earn the world’s opprobrium by asserting dictatorial powers on November 23. Tahrir Square was filled with demonstrators for a seventh day at this writing and members of Morsi’s cabinet have broken with the president’s attempt to eliminate judicial review of executive actions.

It is possible that the Egyptian leader has a Jeykll-and-Hyde political personality, to be sure. But it is also possible that the exigent circumstances of Egyptian governance have pushed Morsi towards risky postures. In this reading, Egypt’s present crisis is less a black comedy than a tragedy in which all available choices lead to a bad outcome.

Morsi inherited from Hosni Mubarak an economy that had gone over a cliff of sorts into deep crisis. His preliminary agreement with the International Monetary Fund for a $4.8 billion loan, announced the day after the Gaza ceasefire, requires painful austerity measures, including the end of some subsidies on fuel and perhaps food, which comprise nearly 30 percent of the country’s budget. Morsi evidently believes that he requires such powers in order to impose austerity. But he has persuaded neither the Egyptian body politic nor prospective investors in Egypt.

The fact that Morsi felt compelled to gamble on a power grab, as well as his failure to execute his design, both beg the question I asked in a September 13 essay for JINSA: “Is Egypt Governable?”

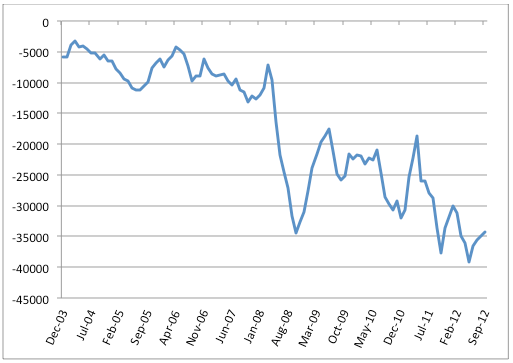

Egypt’s trade deficit of $35 billion a year is offset by tourism receipts of between $9 and $10 billion a year (down from a 2010 peak of $13 billion) and Suez Canal income of slightly over $4 billion. That leaves a gap of $20 billion or so, offset by so-called private transfers-workers’ remittances, private investment flows, and so forth. The annual financing gap could be anywhere between $12 and $20 billion.

As of October, cash-equivalent foreign exchange reserves at the Central Bank were just $7.8 billion, or barely six weeks’ imports, after $1 billion of loans paid in from Qatar and some additional amount from Turkey. Egypt’s finances are running on fumes. Egypt appears to be billions of dollars in arrears to suppliers of diesel, wheat, butane and other essentials, and running through existing stockpiles at an alarming rate. Without a big increase in foreign investment, Egypt cannot last long.

That helps explain President Morsi’s dilemma. His mediation in Gaza helped secure American support for the proposed International Monetary Fund, and might help the Obama administration secure Congressional approval for a $450 million aid package. But his actions in Gaza were read very differently in Saudi Arabia, which views Hamas as an Iranian cat’s paw, and Morsi as a de facto ally of Iran. As Emad El Din Adeeb wrote Nov. 21 in the Saudi news site Asharq Alawsat, “Iran is playing the role of the saboteur in the Arab arena, exploiting issues of regional tension at the time of the Arab Spring revolutions. This is in order to heat up the region so as to disturb Tel Aviv and Washington, prompting them – at the end of the day – to accept negotiations with Tehran on Iranian terms.” And on November 24, Asharq Alawsat’s editor-in-chief Tariq Alhomayed noted that “[Hamas leader Khalid Mishal] came out on the eve of the announcement of the Gaza ceasefire to thank Iran for standing with the ‘resistance’ and supporting it with arms, whilst Ismail Haniyeh also did the same!”

The Gaza affair reinforced Saudi hostility to the Muslim Brotherhood, if any reinforcement were needed. From Riyadh’s vantage point, Mohammed Morsi is not only the leader of a movement that threatens the Saudi monarchy, but also is the patron of a movement that serves Iranian interest. That is of enormous import for Egypt, because Saudi Arabia is the only state with the resources to meet Egypt’s enormous financing requirements.

Saudi news outlets close to the royal family were especially vituperative against Morsi’s power seizure. In Asharq Alawsat on November 26, for example, Abdul Rahman al-Rashed, the head of Al-Arabiya television, wrote that Morsi’s action “is a bombshell announcing the end of the January 25 revolution, and inaugurating the solitary rule of the Muslim Brotherhood. Morsi’s decisions shocked many and united all other Egyptian political forces the same night to warn the public that their president was overthrowing the revolution to become a dictator.”

The day before, Alhomayed, Asharq’s editor, wrote, “One can only be astounded by those in Egypt and the Gulf, specifically some in Saudi Arabia, who are shocked by what the Muslim Brotherhood has done in Egypt, where the President has granted himself new powers not held by any ruler since the pharaohs.”

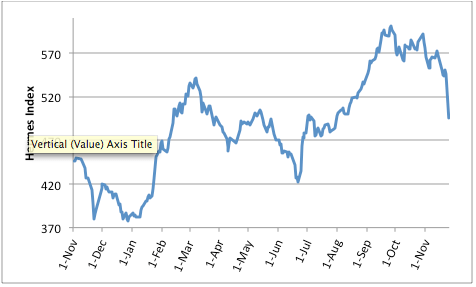

The 9.6 percent crash of Egypt’s stock market on November 25 may demarcate an important turning point. The market value of Egypt’s main stock market index is only $41 billion, which is to say that the whole Egyptian equity market is worth about as much as Starbucks. The market’s sharp recovery during 2012 reflected very small commitments of actual money by foreign (mainly Arab investors). These commitments can be interpreted as political gestures more than value investments. The Egyptian market is expensive by international standards, with a price-earnings ratio of 25 before the crash (vs. 15 before Mubarak’s overthrow). For Saudi and other Gulf State investors, buying Egyptian stocks represented an inexpensive goodwill gesture. When the crash occurred, virtually every stock in the index fell by 10 percent. That sort of indiscriminate mass liquidation also constitutes a political gesture, albeit a negative one.

Some analysts view Morsi’s power grab as an unfortunate miscalculation at just the wrong moment. Bloomberg News, November 26, for example, quoted Elijah Zarwan of the European Council on Foreign Relations as follows:

“Morsi needs political support to institute unpopular economic policies, such as cutting subsidies on fuel or potentially allowing the pound to depreciate against the dollar or the euro. The more polarized the situation gets, the more each side escalates, the harder to imagine the kind of consensus-driven compromise that stands the best chance of enduring and producing the political stability that Egypt needs to get its economy back on track.”

This reading presumes that the “wily fox who has outflanked the military and the vestiges of the Mubarak era by his performance on Gaza,” as the veteran diplomatic observer M.K. Bhadrakumar described Morsi, inexplicably metamorphosed into a bumbler in domestic politics.

An alternative, and more compelling view, is that Morsi believed that dictatorial powers would be required in order to impose the austerity demanded by the International Monetary Fund. Without Saudi support, Morsi had to accept IMF conditions, including reduction of subsidies on fuel, with dire political consequences. Egypt’s economy is barely able to provide basic necessities to the nearly 50 percent of Egyptians who live on less than $2.00 a day. On Nov. 6, the Egyptian Gazette wrote under the headline “Government on alert as wheat crisis looms:”

As wheat prices shoot up worldwide, Egypt, the world’s top grain importer, is squeezed between price hikes and growing demand. There are 2.9 million [metric tons] of grain reserves, enough to cover 117 days, Abu Zeid Mohamed Abu Zeid, Minister of Supply and Home Trade, was quoted by local media as saying when commenting on the possibility that Ukraine could ban grain exports.

It appears that Egypt has been running down stockpiles of wheat, of which it is the world’s largest importer. In June the government announced that it six months’ supply of wheat, or 4.7 million metric tons. As I reported in my Sept. 13 essay, Egypt began running in arrears to suppliers of food and fuel in August. The small amounts of money it has received to date from Qatar ($1 billion with the promise of another $1 billion) and Turkey ($2 billion promised but very little in spendable cash) appear to have kept the country’s liquid reserves around six weeks’ of import coverage. Evidently Egypt was able to improve its wheat stockpile position during November; on Nov. 21, the government claimed that it had 4.6 million metric tons in hand, or 186 days supply. Cooking oil, though, was down to three months’ worth of supplies. The fact that the government feels the need to put out regular bulletins regarding its stockpiles of essential items underscores the extreme fragility of the country’s economic position.

The Morsi government has attempted to justify the inevitable reduction in fuel subsidies by claiming that they largely benefit the wealthiest one-fifth of Egyptians, namely those who can afford cars and air conditioners. No government, though, is likely to enhance its longevity by treating automobile owners as a privileged class.

Rather than viewing the political crisis in Egypt as a diversion on the road to a national consensus on a painful austerity budget, we might view the crisis as prelude to a national crackup over insoluble economic problems. Nothing we have observed in the past two months inspires confidence that Egypt is governable by Mohammed Morsi’s Islamists, or indeed by any competing regime.

David P. Goldman, JINSA Fellow, writes the “Spengler” column for Asia Times Online and the “Spengler” blog at PJ Media. He is also a columnist at Tablet, and contributes frequently to numerous other publications. For more information on the JINSA Fellowship program, click here. For more information on the JINSA Fellowship program, click here.